“Give me a 1,00 words on Frank Zappa.”

Really? A million words would be a good start.

Control Freak(Out)

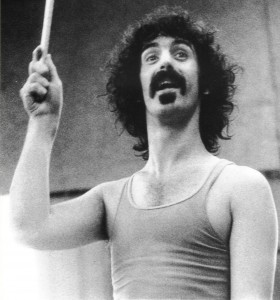

Frank Zappa stands center stage, his back to the audience. Bubble-gum pink tights reveal his long, muscular legs and the crumpled chiffon of his ballerina’s tutu glitters in the spotlight. He raises a conductor’s baton between the thumb and forefinger of his right hand. The baton slices downward, then out to the right and back. His band of 18 journeymen launch into the opening riffs of Dirty Love. Fans scream beyond the footlights.

In a career spanning four decades, Zappa’s sarcastic critique of American culture would take many forms. His virtuosic talent would earn him international acclaim and yet he chose to write about the bizarre and comedic. Some of his song titles from the 1970’s like, The Torture Never Stops, Wind Up Workin’ In A Gas Station, Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow, and Stink-Foot, stood in stark contrast to the schmaltzy love ballads heard on popular radio at the time.

If you believe that genius is akin to madness, Frank Zappa would be their Albert Einstein’s musical godfather. From his early work in film scoring, jingles and experimental rock music, Zappa’s flair for the unconventional was apparent. Later, his tone poem work with French avant-garde composer Pierre Boulez, his collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra, and his Grammy award for the technologically forward Jazz From Hell, would establish him as a major musical figure of the latter twentieth century.

The zany content of Zappa’s music led many to believe he was another drug-addled rock musician from southern California. In fact, the Baltimore native was a confessed conservative who disdained drug use. He famously fired one of his long-standing guitarists, Lowell George, for writing a song about marijuana. Willin’, the song in question, proved to be George’s most memorable hit with his future band Little Feat. Zappa was known as a strict bandleader, and would levy fines on his musicians for missing notes or flubbing executions during performances–easily done on compositions that would run off lead sheets onto music paper adhesive-taped to the sides of the music stands. Only a select group of people can say a man who wore pink tights has fired them or docked their pay.

Frank Zappa’s personal history reads more like a prologue to a serial killer biopic than that of a musical genius. When his family relocated to California in the 1950’s, a teenage Zappa found isolation and alienation. His was perhaps more pronounced, as an east coast transplant and the son of a Greek Arab with an odd last name. He found refuge in music, performing with and later conducting his high school marching band. Although his musical acclaim would come from his searing lead guitar playing, it was this early fluency in percussion that colored his compositional style throughout his career. One song, a rhythmic tour de force, The Black Page, was named for the appearance of the music sheet; so full of notes and musical gestures that little white space remained (while not a commercial hit, the piece would undoubtedly earn him some money in musician fines). The same passion and drive that earned him his conductor’s baton in high school would later manifest in 12-hour days in his recording studio experimenting with nascent multi-track recording techniques.

Early in his career, Zappa performed and composed songs in the doo-wop style of groups like the Drifters and the Coasters. He infused those same chord progressions and vocal harmonies into his songs well into the 1980’s. In the same performance you might hear the salacious lyrics of Bobby Brown Goes Down, sung over decidedly doo-wop backing vocals, segue into Moe’s Vacation, a strident, frenetic orchestration for electric bass and xylophone.

One of his final recordings, Jazz From Hell, was another experiment with cutting edge recording technology. His use of a Synclavier digital sampler was revolutionary for the time, his choice of song titles, like G-spot tornado, was vintage Zappa.

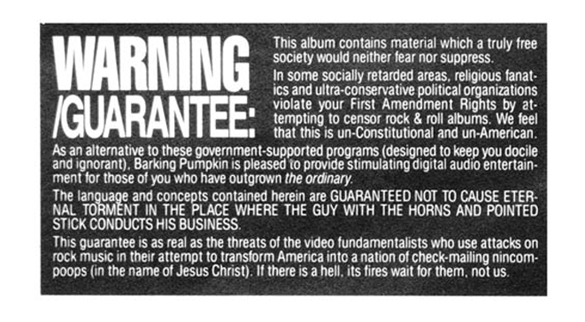

Because of his eclecticism, Zappa remained unknown to the mainstream for much of his career. This changed when he testified before Congress in 1986. Zappa saw the attempted encroachment by the Parent’s Music Resource Council (PMRC) on pop culture as an attack on the First Amendment, and was highly vocal in his opposition. His appearances in the televised hearings and attendant talk shows brought him briefly to the center of national attention. The result of the PMRC’s toil was to create the iconic “parental advisory” label found on many popular recordings. While the intent of this label was to warn parents about a record’s content, it became a watermark for exactly the type of music a rebellious teenager wanted to buy. To illustrate the labels’ absurdity, Zappa’s own record company released Jazz From Hell, an instrumental album, with a parental advisory sticker indicating “explicit lyrics.” Zappa later wrote to Tipper Gore of PMRC, “May your shit come to life and kiss you on the face.”

Arguably the most ironic accomplishment of Zappa’s career came from a scathing indictment of pop culture, of which he found a convenient example in his own living room. Valley Girl featured his daughter Moon Unit talking during the song. Between choruses Moon Unit invoked the language of the time in southern California speak: “Like, fer sure,” or “Totally” and “Bitchin’!” This gimmicky hit reached #32 on the Billboard chart and became Zappa’s biggest single release, much to his dismay. While his intent was to insult, the song was received as a celebration of popular culture and rewarded with commercial success.

Upon his death in 1993, Frank Zappa had released 57 albums in a span of 30 years. From the creation of the first double and triple albums ever released in rock history to his collaboration with international composers and symphonies, Zappa’s musical footprint is as deep as it is wide. Throughout his career, Zappa’s sarcastic narrative was executed with the precision and dedication of a maestro. He was able to pull all of this off and still show up for work in a ballerina’s tutu.